Joanna Cutts has studied at Warsaw University, Vienna University, and was a visiting scholar at Brown University. Her specialization is in the methodology of teaching, curriculum design, and testing. She is the founder of Cogitania, an organization that helps students develop their engagement with the sciences.

I was born in Puck, Poland on the Baltic Sea in 1965. My grandmother, Helena, had married a German, who committed suicide during the war. Tortured by the Gestapo after his death, she still continued to love the grandfather I never met. I live with and in her words: “Joasiu, remember, there are never just good Poles and bad Germans but only good and bad people.”

I write this on February 25th, 2023. Russia’s illegal annexation of Crimea and military support for separatists in 2014 started the war in Ukraine, but until this day last year, it seemed far away. A year ago, I felt as if punched in the stomach. As Russian troops advanced, refugees from Ukraine poured in unimaginable numbers over the four boundary checkpoints into Poland. I could not help but think of my grandmother, of my father’s family who had died in Katyń and Siberia, of the war they suffered. From the very first news, I felt the echoes of their experience in Russia’s full-scale war, and I sought ways to help those who were suffering.

Eliza

On February 23, a day before the war broke out, Eliza had finished her law studies. The same day, she took a train to Kyiv for her internship in the Ukrainian parliament. After the summer, her government was to pay for a master’s program in international law in Holland. The war shattered her plans. As her mother hid in a basement under bombardment in Kharkiv, she joined the stream of refugees, sleeping on floors and trains. In Rzeszów, Poland, an elderly stranger handed her 200€. With it, she made her way to Berlin. On March 14th, an old friend from Berlin emailed me that his family was hosting her.

Putin took Eliza’s internship away, bombed her city, separated her from her mother. Could we defy him in some small way and give Eliza her dream back? Eliza and I met on Zoom. Trying to stop herself from crying, she told me her story. I thought of my older son, the same age. The longer we talked, the more convinced I grew that there was a reason I met Eliza and that there must be a way to help her live her dream. I asked her to trust me, to allow herself to regain hope that Putin’s hand did not stretch far enough to take her dream away from her. I reached out to my Dutch friends and we all met Eliza via Zoom the next week.

We made lists, shared responsibilities, and gave Eliza tasks to work toward her goal. We organized a GoFundMe campaign on Facebook, and I told Eliza’s story to family and friends. Everyone was generous, especially the mother of one of my students, who became Eliza’s patron and took care of not only the rest of her tuition (an essential portion) but also gave her extra money for clothing and books. With everyone’s help, we were able to send Eliza to the Netherlands. A Dutch family hosted her for a week and drove her to Utrecht and Leiden so that she could experience both campuses and choose where she wants to study. Eliza chose Leiden University. She moved from Berlin to Haag and has been studying International Law since September, living with a generous family. A diligent student, she loves every minute of her life there.

Meanwhile, she has met up with her mom twice, once in Berlin and once at my home in Bieszczady, where they were reunited for a week. Her mom is now a refugee in Rzeszow, Poland.

At the same time that I met Eliza, I discovered the Club of Catholic Intelligentsia (KIK), a foundation in Poland that has been actively helping Ukrainians since the Revolution of Dignity in 2014. I had a few Zoom meetings with the secretary of KIK and others directly engaged in helping Ukraine. I was struck with the same feeling I had with Eliza: It was no coincidence that I met them. My American friends and family wanted to support Ukraine and my work helping Ukrainian refugees. They sent money to KIK, which created an even more meaningful and intentional response to the massive wave of Ukrainian mothers, children, and youth moving through our country. In April, KIK opened the Ukrainian School in Warsaw (SzkoUA) for 270 kids, aged 7-17, employing Ukrainian teachers who were also refugees from the war. This initiative allows the shocked and grieving children and youth to continue their school year, to learn and speak in their own language, and maintain an inner connection to Ukraine even if they themselves have been pushed out from their country.

By the beginning of April, I decided I would go to Poland soon. I spoke with the staff of KIK’s Ukrainian initiative about how the philosophy and practice of my teaching in Cogitania together with my knowledge and experience of Visual Thinking Strategies (VTS) could be used in their program. From this collaboration, the teaching program “Summer in the City” was created for Ukrainian kids aged 7 to 17, who came from the active war zones of Kherson, Kyiv, Mariupol, and Kharkiv and needed economic support.

The workshops—120 kids in groups of 15—ran every Monday from 10 am to 4 pm for 7 weeks. All of these children had lost their homes, and some of them had lost one or both of their parents. I chose the theme of “Our Planet,” thinking the story of Earth might be fascinating enough to reengage them in learning and growing.

Marharyta

Nine-year-old Marharyta responded deeply to the theme, yet I noticed her hands moving all the time from left to right on the school table. Both of her parents were fighting for Ukraine; she had been evacuated by a neighbor. I asked Lena (the neighbor) if there was anything I could do to calm Marharyta. What a look on her face I confronted. “Marharyta lost her piano; she played every day since she was four. She performed even in Lviv,” she said. “She has not slept quietly since we arrived in Warsaw.”

Before I came to Poland, some of my American friends gifted me money which I put in a separate Ukraine account to spend at my own discretion. Marharyta’s case called for just such a special use of funds. The wonderful girl received her own keyboard. For the first time since the war started, Marharyta slept soundly.

Oksana Kolesnyk was the Ukrainian head of the Summer in the City initiative. She is a true democratic leader and the head of SzkoUA. Oksana asked me to lead workshops for her teachers to share the techniques and strategies I use in my daily work in Cogitania. I humbly accepted and held the workshops towards the end of August 2022 at SzkoUA. Together, and in subject groups, we looked at ways to see and shape relationships between the students, the teachers, and the curriculum. We developed ideas on how to make the 270 students grow by listening to their own voice. Since the beginning of September, I have been teaching Aristotle, Plato, and Socrates to the 11th grade class. We will continue our conversations when they come to visit me in Bieszczady in May.

The summer and the early fall of last year had a rhythm: doing educational work with Ukrainian refugees for a day or two a week and searching for Ukrainian families, kids, and youth who might need assistance. I knocked on doors, sat with many Ukrainians and their kids, asked what they needed most, listened, and observed. There was always something I could do. I felt like a rake—finding those who were broken, scattered in a foreign country, and in need of help.

Veselovski Family

June 26, 2022. I will never forget this day. In the morning, I went to our carpenter’s workshop. As I approached, the men sat as usual under the old apple tree, but there was someone new.

Vitali was learning how to work with wood, but I sensed he must have been someone else before the war. That evening I invited Vitali with his wife Svieta, their daughter Sofia (14), and their son Stepan (10). They were shy, but each was full of inner light, so I felt. After dinner, I asked the kids to feel at home and take any of the books or drawing materials. Stepan went straight to the 3D puzzles, and Sofia started drawing in the notebook she brought. They reminded me of my Cogitanians: focused, inquisitive, and curious. I left them and went out to Svieta and Vitali. They shared with me how much they lost in just one day. They were worried, awkward, and afraid of trusting, yet full of gratitude to the people of Mchawa (the little village they found refuge in) and especially the village school and its teachers. There was pain oozing out of their story.

Vitali studied geology and economics but couldn’t find work in his profession. Svieta was a fashion designer and a seamstress. Stepan had hearing loss since birth. Prior to the war, they did all in their might to help him develop rather than face a lifetime of challenges. He had an implant over his left ear, but it worked poorly. Sofia was withdrawn, shy but strong. After they left my home, I felt deeply touched by meeting them. Little did I know how close we would become!

On June 29, the Veselovskis were asked to leave their residence a day earlier than they had been told in May. They had an apartment in Rzeszow secured from July 1, but they had nowhere to go for the two days in between.

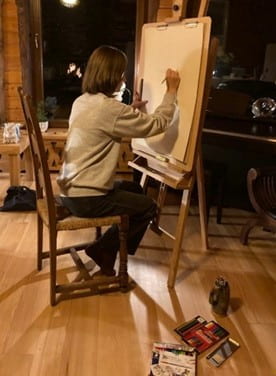

I invited them to stay with me. During their stay, I observed Sofia’s excellent drawings and asked if she would like to go to an art store in Lesko, the nearest town. We bought an easel, paints, art pencils, and paper. I was also hosting Eliza’s mother Valya, who had escaped from Kharkiv. Valya, restored by the company of her fellow Ukrainians, cooked and baked for us that day. For the first time since her daughter left, I could see her gentle smile.

On July 1, the Veselovskis left my house in their very old green Audi with just two backpacks and some food to last a few days. I promised to visit the next day. I called them to learn that their new apartment was clean, but the kitchen was small and lacked any equipment. There was an old sofa and two bare mattresses. The bathroom had a broken washing machine and no soap or towels. The next day, on the way to Rzeszow, I stopped in multiple stores and bought everything necessary to cook, eat, bathe, sleep, and function in a new place. I even stopped at the flower store to buy Svieta an orchid. When I arrived at Forsythia Street in Rzeszow, Sophia, Stepan, Vitali and Svieta greeted me outside with hugs and joy. Their new apartment did start looking like a livable house and would someday become a home.

The next day I took Sofia with me to Warsaw to participate in one of the workshops. She was curious to meet youth her age who, like her, struggled with their new status as a refugee. I showed her the city and took her to a Chopin concert and different sushi restaurants. Sofia loves eating; sushi, and sweets are her favorite!

Meanwhile, Vitali became a cargo driver, home only intermittently. Before the school year started, I traveled with the Vesolovskis once more to Warsaw. With support from KiK, I arranged for Stephan to have a comprehensive ear exam. Deciding against an operation, the doctors exchanged his hearing aid.

The school year started. The transition from a small, personal village school in Mchawa to a 700-student, anonymous school in Rzeszow was challenging. Stepan went from one teacher to six. He didn’t speak Polish and left his two good friends behind in Mchawa. For a child with hearing loss, Rzeszow offered almost nothing. I spent over a week calling Foundation Echo and multiple glotto-speech therapists. Miraculously—again, via an acquaintance of KIK—I found Dr. Beata Naklicka, who teaches Polish to Polish kids with hearing loss. She was skeptical but agreed to meet. As I watched her teaching, I understood that Dr. Naklicka was just who Stepan needed.

As I write this, after five months of therapy, Stepan’s Polish is even better than his sister’s. He has adapted well to his class environment and even found a few friends. Sofia, the promising artist, is working hard to get into the Liceum Plastyczne, the high school of art in Rzeszow. Her health has been an ongoing challenge. Her dermatological problems are almost gone; we are working now on her scoliosis and displaced pelvis – 18 PTs to go. I am in daily contact with Svieta and often also with Vitali. The Veselovski family has become our family.

Vova, Nadia, and Joroslav, Ukrainians from Odesa

It was the 4th of July, my first Monday with the Summer in the City science workshops for the Ukrainian children in Warsaw. I had to meet 120 students, ages 7 to 17, in one day. With two baskets full of 3D science models, pastels, paper, and a poster of the Earth’s interior, I noticed the Uber had arrived. The driver stepped out of the car: “Miss, who are you? Where do you go? What is it?” he exclaimed, wondering at my kit. I recognized his Ukrainian accent. I smiled and said, “My first day to help your children and youth.” Vova looked at me in disbelief. “Pani, I thought Poles are tired of helping us,” he said and told me about his difficult experiences with multiple Polish doctors. As he spoke, his frustration from two years of challenges living in Poland erupted. At 31 years old, he was trapped in the suburbs of Warsaw, with a wife, Nadia, who was not able to walk because of her excruciating back pain, and a son, Jaroslav, just four years old, who due to his chronic nasal infection was not able to go to a kindergarten. Vova was like a roaring lion closed in a cage. With three minutes left until we reached my destination, my head was spinning, and I had that same feeling again. It was no coincidence, me driving with Vova. We arrived. I took 400zl (about 100$) out of my wallet and handed it to him. He became beyond angry. “Pani, do you think, I told you my story to get money from you?”

I took his hand. “It is not for you. It’s for Nadia. All you have to do to earn this money is find a Chinese acupuncture place here in Warsaw, drive Nadia there, and see what happens.” I looked into his face and asked: “Promise?” He nodded. Around 11 pm, I got a message. “Pani, can I call you?” I agreed. “Pani, Nadia is not much better, but she can walk again.” His voice rang with a different timbre. “We can’t afford acupuncture, but a world opened to us. I researched, we ordered books, and we will learn to do it on our own. The doctor gave us a lot of advice,” Vova said, “Thank you.” His words pierced through me. Today, Nadia is still recovering but much better; she has started working, cleaning and organizing offices. Her family once owned land in Odessa. She dreams Ukraine will be free of Russian occupation, and her land will be returned to her. She would open a small boutique hotel and grow a vineyard. Vova, skeptical as always, is less angry. I was able to lend him money to buy his own used car. He is free of debt, and it looks like many of the locks in his cage have been opened. All three of them have a visa to Canada, they might go there one day. With Vova, I felt like a rag clearing a mirror he looked in.

I am going back to Poland on April 25 and will be working as hard as I can to help the Ukrainian youth that feel so trapped and isolated in my country discover that there are paths out of their loss. Despite the seemingly insurmountable challenges and pain wrought by this senseless war, I hope it will be a time of healing and opportunity, with dreams for a bright future.